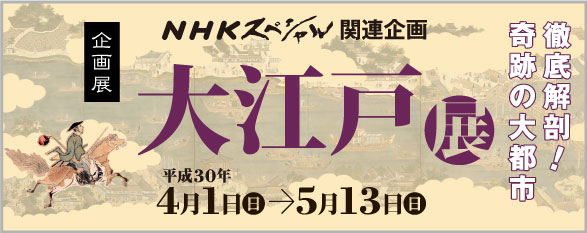

2018.04.01(Sun)〜2018.05.13(Sun)

2018.04.01(Sun)〜2018.05.13(Sun)

■Admission:

Adults: ¥600

College and vocational students: ¥480

High school students, Seniors (65 and over): ¥300

Junior high school students living in or commuting to Tokyo,Elementary school students and younger : Free

■Closed:

Mon. (Except Apr.2,30)

Musashino has been a place associated with traditional poetry, used as utamakura since the ancient times of Manyōshū. The dream-like scenery of waves of pampas grass swaying over its land…. Such was the image of Musashino. It is on the eastern edge of this Musashino Plateau that Edo was located. Much of what Edo looked like before it became a flowering city remains unknown. Perhaps the land of Edo that was imagined during the Edo period was something closer to this picture of Musashino.

The Edo family of the Chichibu Taira clan established its power in Edo, just around the time when Taira no Kiyomori was active in the Imperial capital (present-day Kyoto). The Edo family became shogunal vassals during the Kamakura period and continued to hold power in the region through the Muromachi period. In 1457, Ōta Dōkan of the Ōgigayatsu Uesugi family built the Edo Castle. This was in the beginning of the Sengoku (Warring States) period, and the castle was built as a military base for the southwestern region of the Kanto plains. In 1524, the Edo Castle was seized by Hōjō Ujitsuna of Odawara. Edo was an important base for the Ōgigayatsu Uesugi family in the first half of the Sengoku period, and then for the Odawara Hōjō family in the latter half. Contrary to the lyrical image of pampas grass, Edo had become a vigorous and active place.

In 1590, at the outbreak of the Battle of Odawara, Toyotomi Hideyoshi invaded the Hōjō territory with his massive troops. The Edo Castle was surrendered, and Tokugawa Ieyasu was transferred to Edo.

|

Ōta Dōkan: A Man of Culture who Played the Biwa Lute |

The eastern provinces of the archipelago were known for fortresses that used fewer stone walls. The Edo Castle at the time Ieyasu took over most likely had earthen walls, too. It is much later—after the transition from it being a castle of the Tokugawa, a daimyo under the Toyotomi, to the castle of the Tokugawa shogunal family—that the Edo Castle became a full-fledged castle with stone walls. There is a span of sixteen years between those times, and Tokugawa Ieyasu was the lord of the Edo Castle during this period.

In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu was appointed “Sei-i Taishōgun.” Two years later, his son Hidetada succeeded the office of Shogun. Ieyasu, as the “Ōgosho” (retired shogun), based himself at the Sunpu Castle, while the Shogun Hidetada resided in Edo. In 1606, a tall stone wall was built around Honmaru, and this marked the transformation of the Edo Castle into an early modern castle.

Accordingly, the castle towns began to expand as well. By the Kan’ei era (1624-1644), the castle and the castle town of Edo during the times of Ieyasu had completely transformed itself.

|

Illustrated Map Depicting the Edo Castle in the Early Seventeenth Century |

As goes the saying, “fire and fighting are flowers of Edo,” the city of Edo was frequented by fire. The most notable were the great fires of Meireki (1657), Meiwa (1772), and Bunka (1806), which caused huge destruction to the city. It is amazing how each time after the fire, the city of Edo was reconstructed and continued to flourish as a major city. The knowledge for preventing disasters had also accumulated over the years.

The fire, which were often epoch-making in the city’s history, were depicted in illustrated scrolls and paintings and recorded in numerous documents. These works reveal memories of the horrors of the disaster that have been passed down to this day.

|

Scroll Illustrating a Fire, Known as the “Flower of Edo” |

Many of the places that flourished in Edo were formed around the waters. Edobashi Hirokōji and Ryōgoku Hirokōji are excellent examples, and they were both located at the hub of water and land transportation. Ryōgoku bustled especially during the summer times, when people gathered to enjoy the cool breeze, and the fireworks was a seasonal event that was representative of summer in Edo. Senju and Shinagawa flourished as the first post stations after leaving Edo and served as entryways to Edo.

Many famous places (meisho) were located in the areas around the waters. These places often became subjects of Ukiyo-e prints or pictures for guidebooks describing famous places, and became widely recognized as picturesque landscapes. These illustrations vividly depict the economy, entertainment, and the lively daily lives of the people of Edo.

Edo, which was already a world-class city during the Edo period, goes through a major transformation as a modern city after the Meiji Restoration. Western-style mansions built in spaces among the rows of daimyo residences were symbolic of such an age. The ambiance of Edo that survived this transitional period would be wiped out by the Great Kanto Earthquake and the air raid.

The photographs, the technology for which was introduced during the final years of the Edo period, reveal to us the images of the Edo Castle, the Tokugawa Mausoleum of Zōjōji, and the many features of the city of Edo. Although the purpose for shooting the photographs may have differed—whether it be for preserving cultural property for the later generations or as souvenirs for foreigners—these pictures provide us with an invaluable clues to visualizing Edo that have been long lost.

The last Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu did not spend his time as the shogun at the Edo Castle. He was appointed Shogun in 1866. He was busy dealing with the political disorder in the west. It was in 1867 that he transferred power back to the emperor (“Taisei hōkan”). He was in office for merely ten months, and he remained active in the west throughout that time. When he lost the battle in Toba Fushimi, Yoshinobu escaped Osaka and returned to Edo. However, he could no longer stay in the Edo Castle. The tide was turning toward the Meiji era.

|

Tokugawa Yoshinobu’s Camp Hat in a Unique Design |